Answer: This really depends on who you’re asking. Someone with a more inclusive view of literature would say “yes”, and others with a more exclusive view would say “no”. Both have their own reasons for their positions. Regardless, it does seem that comics and graphic novels are becoming more accepted as serious literature as time goes on.

I remember back in 2016 when Bob Dylan won the Novel Prize for Literature, the whole literary world went up in flames. The reason behind this outburst was the old question of what literature actually is, and what should be considered literature. I mean, it is 2020 and not even the almighty Wikipedia can give us a direct answer. Back then, four years ago, the debate about what is and what is not literature appeared on the front page of every newspaper. Although that discussion is no longer at the forefront, there is still room for debate concerning comic books and graphic novels.

I grew up reading both in parallel and can say that both give me something different to this day. Let’s go deep into each side of the discussion so you can make your own informed decision about it.

So, What Is the Definition of Literature?

Let’s begin by trying to tackle down a definition that has been in the making for millenniums. In fact, the tricky thing about defining literature is that it’s like catching a fish in the water with bare hands. Literature is always moving, growing, mutating, and echoing social and technological changes. In this sense, defining a concept that is continuously changing requires a continuous change of definition either to broaden or shorten its scope. For many, it is the writing quality (AKA “fine writing”) that separates Baudelaire from your grocery list written in small verses. This might seem fine, but who owns the “quality meter” to decide in each case? Literature is currently changing, including new social phenomena and technologies, and so there is a legitimate question about whether or not literature should include Tweets and Facebook posts. This might sound crazy to some, but the way we use the written word has changed greatly, so these questions need to be asked.

The Argument for Why Comics Are Not Literature?

Let’s begin this discussion with the negative part. Those who think that comic books are not literature are mostly basing their opinion into two main pillars:

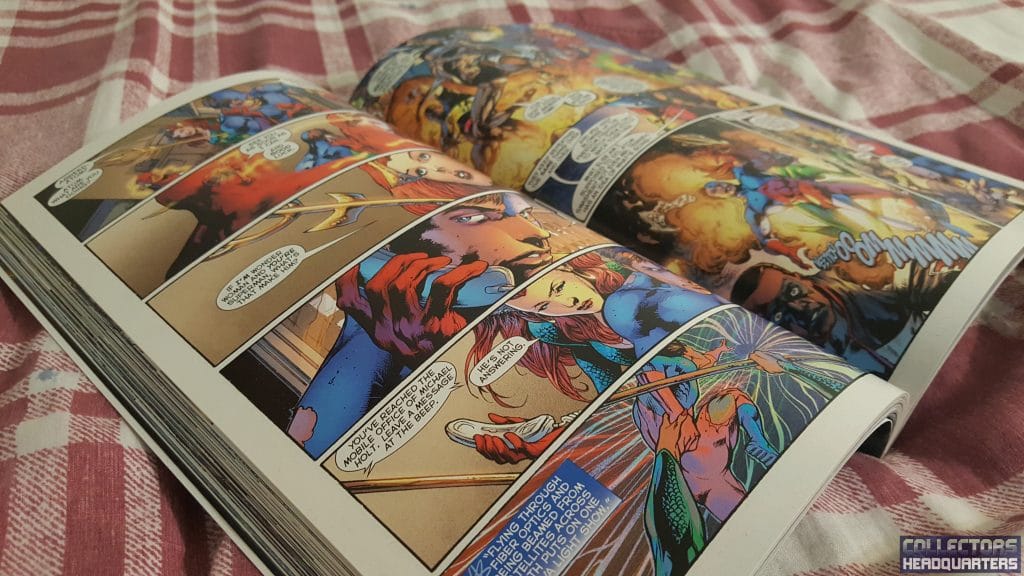

The presence of images -To the presenters of this idea, images cut off one of literature’s biggest merits, which is to play with the reader’s imagination. The stimulus that our brain gets from reading and engaging the imagination to create images is uncanny and not present in graphic novels or comic books. To these people, the fact that comic books attempt to express something through images, excludes comic books from being considered literature.

The amount of words – The amount of words in graphic novels and comic books is very low compared to novels or short stories. This is where most purists find the Achilles heel of comic books and graphic novels. They claim that although a story can be turned into several formats, including the big screen, not all should be considered literature.

The Argument for Why Comics Should be Considered Literature?

On the opposite side of the spectrum, we have a huge number of enthusiasts stating that comic books and graphic novels are literature. Let’s take a look at three of their (many) arguments:

The human timeline – For its supporters, this historical pillar has its foundations in the fact that literature is a human creation going much further back than words. If you take a look at Egyptian hieroglyphics, you get nothing but images. All the great Greek epic tragedies began as an oral tradition and so did Cid Campeador and countless others. In fact, it wasn’t until maybe two centuries ago that most of the population on the planet had access to reading and writing. Gutenberg didn’t invent the press until the 15th century. People presenting this idea state that narrowing literature down to printed words shortens its real life and leaves much of it out.

Structure – For those who back this theory up, the structure on which a comic book or graphic novel relies on to tell a story is the same as you would expect in novels, short stories, and such narratives. You have characters, a plot, a beginning and an ending, dialogue, and more.

Permanence – This last argument states that just like in a regular novel or short story, and opposite to other forms of storytelling (movies, for example), the rate at which the reader receives the information in a comic book is decided by the reader. This means that it is the reader who holds the power to go forward or backward in the story and how much information they want to receive at once.

Broad and Narrow Views of Literature

Let’s make this division citing a man who was able to excel in both terrains. His name is Neil Gaiman and is as well-known for being the writer of great novels such as The Graveyard Book, Stardust, or American Gods among many others. But he is also the writer behind the ten epic books of The Sandman series. He considers himself a storyteller and seems willing to stretch and transcend the boundaries of traditional literature to tell whatever story is in his mind.

This is a broad view of literature in which the story is the ruler and the literary gender follows and not the other way around. Literature serves the storytelling purpose with the tools at hand, whichever they are.

On the other hand, we have Ryan Duggan, explaining to us in this editorial that although he thinks there is artistic integrity in graphic novels they can’t be considered literature being so far away from just written words. He also states that graphic novels belong to the same group as movies because images tell the story and words act as a secondary force.

Both views on literature are opposing and perfectly valid at the same time. Those aligning with Neil Gaiman’s views walk under a broad concept of literature while those following Ryan Duggan’s words work with a much narrower notion leaving a lot of written material out. You get to pick a side.

The One Book That Changed It All

The very reason you have to pick a side is, arguably, a single book. On April 19th, 1954, the book Seduction of the innocent by psychiatrist Frederic Wertham reached the streets to change comic book history forever. The book was the result of scientific analysis with children to show how comic books were a bad influence on them. He drew from classics as well as from the newly-arrived crime and horror comics.

The Impact of Seduction of the Innocent

Senator Estes Kefauver took the book as a platform to increase the reach of his own beliefs. He was considered to be a mob hunter and found in Wertham’s words a great vessel to deliver his message. Furthermore, he appeared before the Subcommittee of Juvenile Delinquency of the Senate to make claims on how comics lead youth to become delinquents. He stated that comics were even more dangerous than Hitler himself for children. Just as a note, remember that this was the early fifties and the memories of WWII were still very fresh. Hitler was still a threat to the world and especially for the US Society. This political move by Kefauver paid off with The New York Times presenting a negative view of comics on their front page.

The Creation of the CCA

One of the main consequences of the book was the creation of the Comics Code Authority in 1954. This was an entity designed to regulate comic book content. It wasn’t created by the government, but by the Comics Magazine Association of America. This means that the comic publishers were censoring themselves. If the CCA approved of the content, the stamp would appear on the front cover. This act brought 15 comic publishers to bankruptcy in the same year. You might not believe this, but the CCA was still stamping comics in 2011 but was defunct after DC Comics along with all major publishers stopped caring about it.

Controversy on the Method and Content

The comic industry didn’t suffer legally the consequences of the book, because the government didn’t act upon it. That being said, Kefauver’s hearing was broadcasted by the TV and the damage to the comic industry was far bigger anyone could have ever imagined. Although it was given an initial status of truth, there were several areas scholars found weaknesses; let’s see some of the most relevant ones:

Sample size and background – In 2012 Carol L. Tilley published a study in which she stated that the population used as a sample for the study were New York children institutionalized for previous behavioral problems. This is to say that he tested the bad influence of comics on kids institutionalized for bad behavior. For Tilley, Wertham didn’t isolate the impact of comics with rigorous scientific objectivity, but rather amplified a simple fact: kids love reading comics (regardless of their behavior).

Sexuality – There were two important pillars in Wertham’s book aiming to condemn homosexuality (seen back then as a deviation): Batman & Robin’s presumed gay relationship and Wonder Woman’s strength and independence making her a lesbian. For Tilley, none of these arguments had any scientific roots and nowadays are obsolete and inconsequential.

Taking out of context – There were some judgments made over characters to present them as harmful which were taken out of context according to Tilley. For example, the comparison between the Blue Beetle and Kafka’s Metamorphosis was biased because the Blue Beetle is a man in a suit, not a real bug.

What about Literature During that Time?

Although the damage made on comic books was irreparable, it was not the only industry affected. Those who divide “real literature” from comics will indeed find a point of contrast to their argument here. Let’s take a piece of work as an example: Howl by Allen Ginsberg.

The Howl Example

Howl was first presented to the public in 1956 but was immediately forbidden and faced public trial. Just like it happened with comics, the vivid literary underground scene was showing society’s true colors to the public and not everyone was willing to let that happen. Poetry in the hands of the beat generation became disruptive and hence, faced censorship.

Why is the Howl example particularly important for the discussion about comics being literature if it is a poetry book? Well, just like with comics, what was being discussed in the trial was the “literary merit” of the author when writing the piece. If the defenders could prove to the judge that it wasn’t a pornography book, but a “serious literary piece” that should be read by the public, then it could be printed. In fact, that was what saved Howl from the ban. The concept of “fine writing” became the author’s ally facing the jury.

Howl succeeded where comic books couldn’t and its “pornography” tag was removed. The book became a hit still in print today after approximately 1,000,000 units sold.

The Pulitzer

Just like Wertham’s book was a pivotal point for public opinion in terms of comic books, the Pulitzer Prize given to Art Spiegelman for Maus put comic books in the “serious literature” row again. The same way Dylan’s Nobel Prize in Literature generated discussions that reached the front page of most newspapers, this award given to Maus brought back a discussion that was long gone and forgotten.

The year was 1991 when the graphic novel got published. It won the prize the very next year, 1992. No other graphic novel won it again. The contents of Maus talk about the events that happened in World War II—replacing Germans with cats, Jews with mice, and Polish as pigs. Although the author utilizes anthropomorphism to show the qualities of the characters, this graphic novel is based on a true story that was told to him by his father. This resonated with a broader audience than is typical of comic books. Maus has sold over a million copies since it was first pressed.

The Trilogy That Began the New Period

Maus wasn’t alone in inaugurating a new period in comic books and graphic novels reputation. The trilogy formed by Watchmen and The Dark Knight Returns challenged most of the skepticism surrounding comic books in general. A long-built bias ignoring underground comics began to break and more adult-oriented material started making it to the surface. This positive view of comic books was also helped with the number of sales generated. Companies began funding longer, more serious graphic novels and “serious” writers like the afore-mentioned Neil Gaiman could pour all their talent into comic book format. The Sandman was a great example of this new era of comics and graphic novels.

The Role of Movies

The movie industry echoed on the ground-breaking graphic novels of each time. For example, Batman: The Dark Knight Returns served as inspiration for Joel Schumacher, Christopher Nolan, and Zack Snyder in blockbusters like Batman Forever, Batman Begins, Batman Vs Superman and more. This arrival to the big screens helped propel these graphic novels into mainstream sales again after the beginning of the 21st Century.

Arguably, those who enjoyed the movie as a superhero story with a strong plot, found more than meets the eye in graphic novels, taking them more seriously. Writers like Alan Miller saw several of his graphic novels taken to the big screen like Ronin, Sin City, 300, and Daredevil just to name a few. Another important name in this sense is Alan Moore, responsible for graphic novels such as Watchmen, V for Vendetta, and Swamp Thing among many others.

The role of the movie industry supporting graphic novels to create blockbusters is just another piece in the puzzle that helped comics reach a new era in the world.

Times Are A-changin’

Thanks to these pivotal moments described above it is good to say that times are changing in the literary world. In this very interesting video of a TED talk by teacher and artist Gene Yang, he explains the impact of Seduction of the Innocent and how it gave the whole industry a bad name for schools, colleges, and other formal environments who removed comics from their curricula. He also proudly explains how they are slowly making their way back into the classrooms.

I remember reading the Kingdom Come saga and thinking “this is something else”. Slowly, but at a steady pace, this same feeling I got started happening to those in charge of literature departments and schools.

We can speak about not only comics but about a rising culture with a higher sensibility for imagery rather than words. Arguably, a generation that grew up with a screen to their face needs comic books and graphic novels to act as a bridge and close the gap between images and words.

The future is not something anyone can predict but one thing is for sure, it is not slowing down technology-wise. Comic books and regular books and even this discussion can grow obsolete when new modes of storytelling come upon us. Culture in general and literature will echo the coming revolutions creating new ways to reach people.

Until then happy reading!